A new peer-reviewed report (Rode et al. 2014 [in print] 2013, accepted), released last month (announced here), documents the fact that polar bears in the Chukchi Sea are doing better than virtually any other population studied, despite significant losses in summer sea ice over the last two decades – even though the Polar Bear Specialist Group (PBSG) said this population was declining (Obbard et al. 2010).

Rather than this good news being shouted far and wide, what we’ve seen so far is a mere whisper. The strategy for suppressing the information appears to have several parts: make it hard to find; don’t actively publicize it; down-play the spectacularly good nature of the news; minimize how wrong they were; keep the focus on the future.

Something similar happened with the newly-published paper on Davis Strait bears (Peacock et al. 2013, discussed here and here) but the news there wasn’t quite so shockingly different from expected. The suppression of good news stands in marked contrast to anything with a hint of bad news, which gets reported around the world — for example, Andrew Derocher and colleagues and their “prepare now to save polar bears” policy paper in February, 2013.

US Fish & Wildlife biologist Eric Regehr, co-investigator of the Chukchi study and co-author of the newly-published report, wrote an announcement about the paper. It wasn’t a real press release, since it was not actually sent to media outlets. It was a statement, with a brief summary of the paper, posted on a regional US Fish & Wildlife website, with no mention of lead author Karyn Rode. Not surprisingly, lack of active promotion = no media coverage.

The posted announcement also down-played how well the Chukchi bears are doing. In fact, the news documented in the paper is much better than any of them let on: Chukchi polar bears are doing better than virtually all other populations studied.

But Regehr also had to do some damage control to counter the evidence this paper contains of how wrong they had all been — not only about the Chukchi population today but about their predictions for polar bears in the future.

After all, the computer models used to predict a dire future for polar bears combined the Chukchi Sea with the Southern Beaufort, as having similar ice habitats (“ice ecoregions”). The published paper and Regehr’s statement now say these two regions are very different and that polar bear response to loss of sea ice is “complex” rather than a simple matter of less summer ice = harm to polar bears. Regehr goes on to say that polar bear scientists expected this would happen. I call total BS on this one, which I explain in full later (with a map).

Finally, Regehr’s statement emphasizes that good news for 1 subpopulation out of 19 today should not be celebrated because the overall future for polar bears — prophesied by computerized crystal balls — is bleak. Focus on the future, they say. Did they forget that for years they’ve been telling us that polar bears are already being harmed and that this foreshadows what’s to come? Now we have the results of yet another peer-reviewed study showing bears not being harmed by declines in summer ice (see the full list here).

So, in the end, all of this double-talk and contradiction is not just about suppressing this particular paper. There’s much more at stake.

The Rode et al. Chukchi paper is strong evidence that their predictions of a grim future for polar bears – based on theoretical responses to summer sea ice declines that should already be apparent – have been refuted by their own studies. It’s no wonder they want to keep the media away from this story.

Details below. [Update September 11, 2013: another news outlet picks up the story, see Point 2 below]

Here is the first paragraph of the statement composed by the paper’s co-author Eric Regehr, a wildlife biologist with the FWS (pdf here):

“Polar Bears in the Chukchi Sea Doing Well, Despite Sea Ice Loss”

August 22, 2013

Climate change is the greatest long-term threat to polar bears. On May 15, 2008, the U. S. Fish & Wildlife Service (Service) listed the bear as threatened throughout its range under the Endangered Species Act. If loss of sea ice habitat continues, most populations of this iconic species are expected to decline or disappear by the end of the 21st century. But the path to that point might not be straightforward. In fact, scientists expect a lot of variation in when, where, and how the effects of sea ice loss will appear. According to a new study, by some measures one of the Arctic’s nineteen polar bear populations is doing quite well. Read more. [my bold]

Notice that all the prophesied doom and gloom comes first and the watered down good news is not mentioned until the very last sentence, which could hardly be more innocuous.

I’ve broken down Regehr’s entire statement, as it reflects a strategy of suppressing good news and preserving the “message” that polar bears are threatened with extinction:

Point 1 – No mention of first author Karyn Rode. Why not mention the paper’s first author? That’s not just rude, it’s unprofessional. I can’t imagine her being happy about it but what can she do? Her employer and senior male colleagues would rather her important research remain as much out of the limelight as possible. While it may make it more difficult for people to find the paper if they don’t have the first author’s name, but I doubt that’s the only reason.

Point 2 – Don’t actually promote it. Regehr’s statement was simply posted on the Alaska region website of the Fish & Wildlife Service. The first paragraph, quoted above, appears as one item on a rotating page of “news” (here) that will eventually move to the bottom and disappear from view (pdf here). In other words, it doesn’t have a separate page with its own unique address. The item was not posted on the FWS Alaska Facebook page or the USGS Alaska Science Center website or its Facebook page (as of Sept 6). This treatment virtually guaranteed that the media wouldn’t hear about it – and neither would the general public.

How far did the good news spread? As of September 6, I found only two stories online based on Regehr’s FWS statement (SitNews simply reprinted it). Greenpeace-activist-turned-activist-science-writer Kieran Mulvaney was the first to pick up the FWS statement (via a tweet by Geoff York on Aug 28th). He basically reiterates Regehr’s FWS statement but he does at least mention Karyn Rode’s contribution (Discovery News, Aug. 31, 2013, “For polar bears, some places better than others”).

Polar Bears International picked up the story (September 2), with the eye-catching title “Chukchi Sea polar bears.” It starts out with the same muted version of the good news as the FWS statement and extensively quotes polar bear biologist Steve Amstrup, their chief scientist and primary spokesperson, who emphasizes the FWS “we expected this to happen” (debunked in Point 4 below) and the “focus on the prophesied future” memes (Point 5).

Update September 11 2013: Alaska Dispatch (A. Feidt, Sept.10) has a story [h/t commenter nvw] that includes an interview with Eric Regehr (“Chukchi polar bear population remains healthy as ice coverage lessens”).

No mention of the “we knew this would happen” meme but also, no mention of the fact that Chukchi bears are doing better than all but one other population that’s been studied. No mention of Karyn Rode either. It seems to have been picked up by a few places via Associated Press (Kentucky; Anchorage; Everett, Washington State)

Point 3 – Down-play the good news. This is how the FWS statement describes the research results:

“The study finds that body condition (i.e., the size and fatness) and reproductive rates of Chukchi Sea bears remained stable or improved over the past 20 years, despite large sea ice declines. Also, Chukchi Sea [CS] bears currently have better body condition and higher reproduction than their neighbors in the southern Beaufort Sea [BS], north of Alaska, where the USGS has studied bears for over 30 years. Although diets were similar for the two populations, the Chukchi Sea bears had greater access to food in the spring.” [my bold]

Compare this to what it says in the paper’s abstract:

“Bears in the CS exhibited larger body size, good body condition, and high indices of recruitment compared to most other populations measured to date.” [my bold]

And in the paper itself:

“Our spring 2008-2011 observations of CS polar bears in good condition and with high recruitment [litter production] are consistent with autumn observations of bears from this population on Wrangel Island during the same period (Ovsyanikov and Menyushina, 2010). …the majority of the CS population dens on Wrangel Island or nearby smaller Herald Island.

…These spring COY litter sizes [for Wrangel Island in 2007 and 2009] are among the highest reported for 18 of 19 polar bear populations. [my bold]

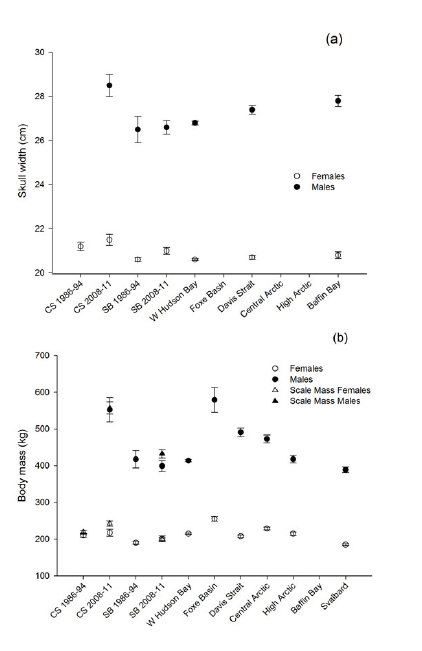

In fact, the body condition and litter sizes of Chukchi polar bears (more details here and here), which are the primary indicators of population “success” – were not only unchanged or improved after 20 years but better than virtually all other populations that have been studied, including Southern Beaufort, Western Hudson Bay, Davis Strait, Baffin Bay, Gulf of Boothia/M’Clintock Channel, Lancaster Sound and Svalbard (see Fig. 1 below).

Only for weight did bears in one other population (Foxe Basin) surpass Chukchi animals [come to think of it, who knew Foxe Basin bears were in such good condition?]

So, the good news is phenomenally better than the statement lets on.

Figure 1. Skull width, which measures amount of stored fat (a) and weight (b) of Chukchi male and female polar bears compared to other populations measured. CS, Chukchi Sea; SB, Southern Beaufort; Central Arctic = parts of Gulf of Boothia and M’Clintock Channel; High Arctic = Lancaster Sound.

Point 4 – We expected this to happen. This is entirely not true.

From the paper:

“…the response of polar bears to sea ice loss may vary temporally and geographically, due to variation in ecosystem function and in the life history strategies (Amstrup et al. 2008).”

From the first paragraph of the statement:

“In fact, scientists expect a lot of variation in when, where, and how the effects of sea ice loss will appear. [my bold]

And from the PBI story, their chief scientist spokesman Amstrup:

“The findings are exactly in line with our predictions,” says Dr. Steven C. Amstrup, our chief scientist, who led polar bear research in Alaska until 2010. “The near-term effects of global warming on sea ice and polar bears are expected to differ geographically….

In other words, they knew all along this would happen. Really?

Actually, the shortest-term prediction that has been made is 25 years in the future, as explained in the Amstrup et al. (2008) paper cited by Rode et al.: there have been no “short-term” predictions, only assertions that some polar bear populations are currently suffering.

The variation they “expected” was between defined ice ecoregions, not within them (see Fig. 2 below), 25-95 years from now.

For example, if warming continued into the mid-21st century, they proposed, bears in the Central Canadian Archipelago, the Arctic Basin and East Greenland (“Archipelago” and “Convergent” ice regions, gold and blue on the map) would likely do better because thick, multiyear ice would be replaced by first year ice. Populations in those regions might increase as a consequence, even though populations to the south (in “Divergent” and “Seasonal Ice” regions, purple and green on the map) would decline or be extirpated (Amstrup 2011; Amstrup et al. 2008, 2010; Obbard et al. 2010).

They did not expect that bears currently living near the southern limits of their range, in so-called Divergent and Seasonal Ice ecoregions (including Chukchi Sea and Davis Strait, see Fig.2 below), would do well – or better – despite large declines in summer sea ice.

Durner et al. (2009:41), in one of the prediction papers used to support the upgrade of polar bears to “threatened” status in the USA, said that:

“…within the Divergent ecoregion, rates of decline are projected to be greatest in the Southern Beaufort, Chukchi, and Barents Sea subpopulations.”

In other words, the prediction schemes used to get polar bears listed as threatened under the US Endangered Species Act treat the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas as identical habitats that would be among the worst affected. Now they claim these region are significantly different.

Figure 2. Sea ice ecoregions used to predict the future of polar bears (this version from Rode et al. 2013 (the Wakefield presentation). See also Amstrup 2011; Amstrup et al. 2008; 2010; Durner et al. 2009;

Point 5 – Focus on the future. Regehr and Amstrup insist that the results of the Chukchi study should not be seen as an indication that all or most polar bear populations can do well despite sea ice declines in summer [even though Regher’s statement acknowledges (see Point 3) that it is the amount of food in the spring that made the difference for Chukchi bears].

For years, they’ve been telling us that polar bears are already being harmed and that this foreshadows what could happen in the future. If things are so good now, despite declines in summer sea ice, what does that say about the accuracy of their predictions?

In reality, the Rode et al. Chukchi paper is strong evidence that their predictions of a grim future for polar bears – based on theoretical responses to summer sea ice declines that, we are told, are already in play – have been refuted by their own studies. It’s no wonder they want to keep the media away from this story.

References

Amstrup, S.C. 2011. Polar bears and climate change: certainties, uncertainties, and hope in a warming world. Pgs. 11-20 in R.T. Watson, T.J. Cade, M. Fuller, G. Hunt, and E. Potapov (eds.), Gyrfalcons and Ptarmigan in a Changing World, Volume 1. The Peregrine Fund, Boise, Idaho. http://dx.doi.org/10.4080/gpcw.2011.0100

Amstrup, S.C., DeWeaver, E.T., Douglas, D.C., Marcot, B.G., Durner, G.M., Bitz, C.M., and Bailey, D.A. 2010. Greenhouse gas mitigation can reduce sea-ice loss and increase polar bear persistence. Nature 468:955-958. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v468/n7326/abs/nature09653.html

Amstrup, S.C., Marcot, B.G., Douglas, D.C. 2008. A Bayesian network modeling approach to forecasting the 21st century worldwide status of polar bears. Pgs. 213-268 in Arctic Sea Ice Decline: Observations, Projections, Mechanisms, and Implications, E.T. DeWeaver, C.M. Bitz, and L.B. Tremblay (eds.). Geophysical Monograph 180. American Geophysical Union, Washington, D.C. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/180GM14/summary and http://alaska.usgs.gov/science/biology/polar_bears/pubs.html

Durner, G.M., Douglas, D.C., Nielson, R.M., Amstrup, S.C., McDonald, T.L. and 12 others. 2009. Predicting 21st-century polar bear habitat distribution from global climate models. Ecological Monographs 79:25-58. http://www.esajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1890/07-2089.1

Obbard, M.E., Theimann, G.W., Peacock, E. and DeBryn, T.D. (eds.) 2010. Polar Bears: Proceedings of the 15th meeting of the Polar Bear Specialist Group IUCN/SSC, 29 June-3 July, 2009, Copenhagen, Denmark. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge UK, IUCN.

Rode, K.D., Douglas, D., Durner, G., Derocher, A.E., Thiemann, G.W., and Budge, S. 2013. Variation in the response of an Arctic top predator experiencing habitat loss: feeding and reproductive ecology of two polar bear populations. Oral presentation by Karyn Rode, 28th Lowell Wakefield Fisheries Symposium, March 26-29. Anchorage, AK. Abstract below, pdf here.

Rode, K.D., Regehr, E.V., Douglas, D., Durner, G., Derocher, A.E., Thiemann, G.W., and Budge, S. 2013 (accepted). Variation in the response of an Arctic top predator experiencing habitat loss: feeding and reproductive ecology of two polar bear populations. Global Change Biology. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.12339/abstract

Rode, K.D., Regehr, E.V., Douglas, D., Durner, G., Derocher, A.E., Thiemann, G.W., and Budge, S. 2014 [in print]. Variation in the response of an Arctic top predator experiencing habitat loss: feeding and reproductive ecology of two polar bear populations. Global Change Biology 20(1):76-88. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.12339/abstract [updated February 9 2014]

Rode, K. and Regehr, E.V. 2010. Polar bear research in the Chukchi and Bering Seas: A synopsis of 2010 field work. Unpublished report to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of the Interior, Anchorage. pdf here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.