Researchers at the Norwegian Polar Institute have finally updated their spring data, which show male polar bears in 2024 were even fatter than they were in 1993 and litter sizes of new cubs were just as high, despite continued low sea ice in the region over the summer months especially.

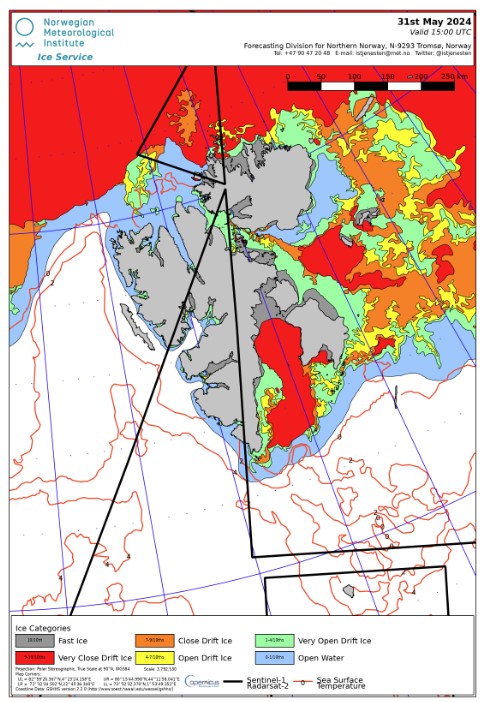

The region

Area surveyed in August 2015 where polar bears were found, as shown below (Aars et al. 2017) included the pack ice north of Svalbard. Spring surveys done in March/April appear to include only land areas of the Svalbard archipelago.

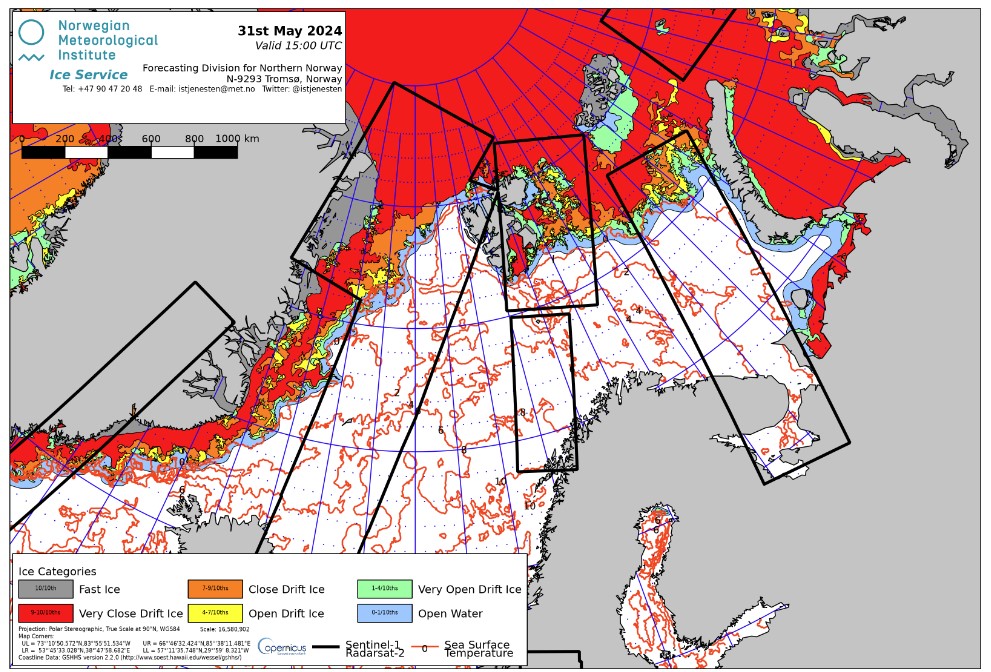

Sea ice conditions

This year, at the end of May around Svalbard:

In the wider area of the Barents Sea:

Unfortunately, Norwegian Ice Service data only go back to 1997, so we can’t see specifically what conditions were like in 1993, but other sources show sea ice was more extensive then in all seasons.

Hopen Island, circled on the map below, is so far south that bears are only able to den there when Barents Sea fall ice is extensive (Andersen et al. 2012; Derocher et al. 2011).

The graph below, copied from the MOSJ polar bear webpage, shows the number of days from 1979-2024 when sea ice cover around Hopen Island in the fall (1 October – 31 December) exceeded 60%. In the early 1990s, ice cover around Hopen was unusually abundant (black line). By 1994, many females used the island for maternity denning (peak of blue line) but after 2007, few if any bears did so due to lack of sea ice.

Spring 2024 Data

The newest Norwegian data show that cub recruitment (the number of cubs per litter), copied below, was as high in 2024 as it has ever been and just as high as it was in 1993 before sea ice declines began, although in 2023 it was the lowest since 1993.

Data for the body condition of male bears in spring (March-May, copied below), which has been tracked since 1993, show a slight decrease up to the year 2000.

However, after 2000, body condition increased over the next two decades to 2024 despite a significant decrease in sea ice cover, leaving bears in better condition overall in 2024 than they had been in 1993 and any year since.

Conclusions

This 2024 data from male Svalbard bears mirrors that of female bears captured up to 2017, which showed a similar pattern (Lippold et al. 2019): less sea ice in recent years has meant bears have been in better condition than they were in the 1990s when there was more sea ice.

Lippold and colleagues (2019: 988) stated this clearly for female polar bears (my bold]:

“Unexpectedly, body condition of female polar bears from the Barents Sea has increased after 2005, although sea ice has retreated by ∼50% since the late 1990s in the area, and the length of the ice-free season has increased by over 20 weeks between 1979 and 2013. These changes are also accompanied by winter sea ice retreat that is especially pronounced in the Barents Sea compared to other Arctic areas. Despite the declining sea ice in the Barents Sea, polar bears are likely not lacking food as long as sea ice is present during their peak feeding period. Polar bears feed extensively from April to June when ringed seals have pups and are particularly vulnerable to predation, whereas the predation rate during the rest of the year is likely low.”

As I’ve explained previously, this is almost certainly due to the fact that less sea ice in summer causes increased primary productivity — more plankton feeds more fish, which feeds more seals — which produces an abundance of seals for polar bears to feed on when sea ice is present in the spring (Crockford 2023; Frey et al. 2022).

The Norwegian authors concluded their 2024 polar bear report by stating [my bold]:

Even though the loss of sea ice has been marked around Svalbard in recent years, and is expected to continue in the coming decades, the size of the subpopulation may still be below the carrying capacity.

It is therefore possible that the subpopulation currently is still growing, or at least is stable, even though the availability of habitats has become poorer for much of the year. …

Observations so far are unable to document that changes in the climate have had clear effects on the subpopulation.

References

Aars, J., Marques,T.A, Lone, K., Anderson, M., Wiig, Ø., Fløystad, I.M.B., Hagen, S.B. and Buckland, S.T. 2017. The number and distribution of polar bears in the western Barents Sea. Polar Research 36:1. 1374125. doi:10.1080/17518369.2017.1374125

Andersen, M., Derocher, A.E., Wiig, Ø. and Aars, J. 2012. Polar bear (Ursus maritimus) maternity den distribution in Svalbard, Norway. Polar Biology 35:499-508.

Crockford, S.J. 2024. State of the Polar Bear 2023. Briefing Paper 67. Global Warming Policy Foundation, London. Download pdf here.

Derocher, A.E., Andersen, M., Wiig, Ø., Aars, J. and Biuw, M. 2011. Sea ice and polar bear den ecology at Hopen Island, Svalbard. Marine Ecology Progress Series 441:273-279.

Frey, K.E., Comiso, J.C., Cooper, L.W., et al. 2022. Arctic Ocean primary productivity: the response of marine algae to climate warming and sea ice decline. 2020 Arctic Report Card. NOAA. DOI: 10.25923/Oje1-te61 https://arctic.noaa.gov/Report-Card/Report-Card-2022/Arctic-Ocean-Primary-Productivity-The-Response-of-Marine-Algae-to-Climate-Warming-and-Sea-Ice-Decline

Lippold, A., Bourgeon, S., Aars, J., Andersen, M., Polder, A., Lyche, J.L., Bytingsvik, J., Jenssen, B.M., Derocher, A.E., Welker, J.M. and Routti, H. 2019. Temporal trends of persistent organic pollutants in Barents Sea polar bears (Ursus maritimus) in relation to changes in feeding habits and body condition. Environmental Science and Technology 53(2):984-995. Get the paper here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.