Increased primary productivity in the Arctic generated by reduced summer sea ice has continued into 2025, according to NOAA’s annual Arctic Report Card published yesterday, which means Arctic seals and whales, walrus, and polar bears will continue to flourish.

Don’t look for that take-home in the legacy media, since they will all focus on the bits of the report that feed a doom-mongering narrative.

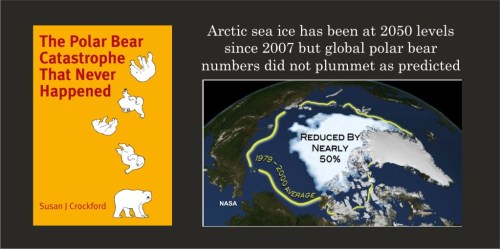

September sea ice extent has continued to stall, rather than plummet as predicted (Table 1: eleventh lowest average September extent since 1979; 4.75 mkm2), although they don’t come out and say so. NSIDC has stopped producing monthly sea ice reports due to budget cuts in late September 2025.

From the Report Card highlights [my bold]:

- From 2003 to 2025, phytoplankton productivity spiked by 80% in the Eurasian Arctic, 34% in the Barents Sea, and 27% in Hudson Bay.

- Plankton productivity in 2025 was higher than the 2003-22 average in eight of nine regions assessed across the Arctic.

And from the report on primary productivity itself:

All regions, except for the Amerasian Arctic (the combined Chukchi Sea, Beaufort Sea, and Canadian Archipelago), continue to exhibit positive trends in ocean primary productivity during 2003-25, with the largest percent changes in the Eurasian Arctic (+80.2%), Barents Sea (+33.8%), and Hudson Bay (+27.1%).

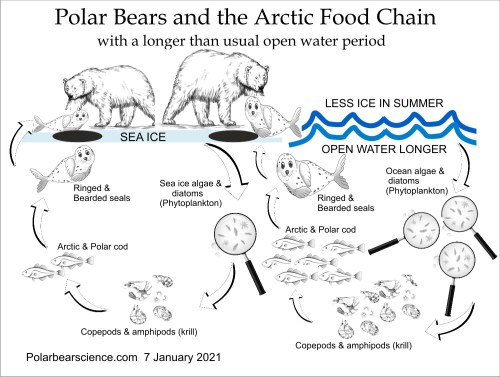

I’ve explained previously how and why this works: less summer ice = more plankton, which means more food for all marine life.

This explains why the catastrophic decline in polar bear numbers predicted in 2007 never happened.

PS. If you haven’t already, check out my new wolf attack thriller, DON’T RUN. There’s probably still time to order and get a before-Christmas delivery.

You must be logged in to post a comment.