[Update: Feb. 10 2013. I have corrected an oversight in the summary tables – the originals neglected to indicate that the Barents Sea subpopulation is shared between Norway and Russia (not controlled by Norway alone). Here is revised Table 1 and revised Table 2. ]

[Update 2: Sept. 26, 2013. See “Global population of polar bears has increased by 2,650-5,700 since 2001″ for further insight. I have also made slight corrections to the tables below, now marked Version 3.]

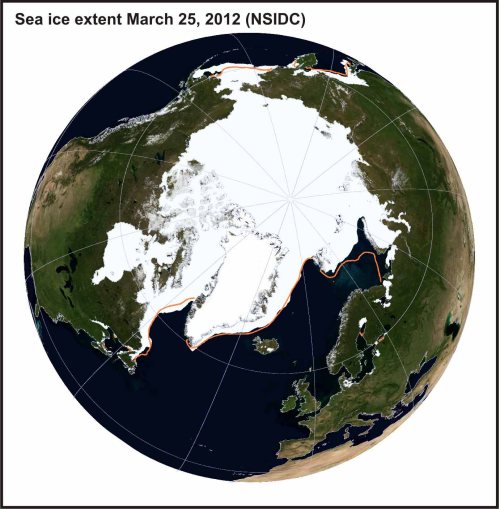

A couple of weeks ago, a news report appeared highlighting an interview with Russian biologist Nikita Ovsyannikov, deputy director of Russia’s polar bear reserve on Wrangel Island in the Chukchi Sea. This is what the news report said:

“He [Ovsyannikov] guessed the number of bears around the Chukchi Sea, which also sometimes migrate in small numbers to western Alaska, had dropped over the past three decades from “about 4,000 to no more than 1,700 at best.”

See Kelsey’s comments over at Polar Bear Alley and the comment I left there, here and my related previous post here

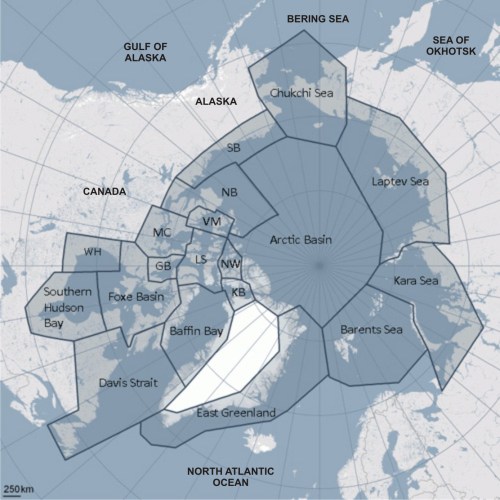

This media focus on Chukchi Sea polar bear numbers caught my attention because I had recently spent some time going through the 15 Polar Bear Specialist Group (PBSG) meeting reports in an effort to summarize the population estimates they provided. This international group first met in Fairbanks, Alaska in 1965 to advance and coordinate polar bear research and conservation under the auspices of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the Species Survival Commission (SSC). I knew that according to the PBSG, the population of the Chukchi Sea is zero – that is, no Chukchi bears are included in the official total of 20,000-25,000 bears because no reliable survey had ever been done. Ovsyannikov’s statement to the press encouraged me to finish my summary of the population estimates in the PBSG meeting report tables.

This was not an easy task, in part due to the virtually constant changes in presentation style and format in the tables used to present the data (which appeared first in the 1981 report). For example, even between the 14th (2005) and 15th (2009) meeting reports, the population data table presents the subpopulations in different order and swaps the position of two critical columns (“status” and “observed or predicted trend”), making it extremely difficult for readers to do a quick comparison between years.

So I simplified the 2009 table (the most recent available), leaving out the future predictions as irrelevant to questions about current status. I included some population estimates and status assessments from previous reports to show the changes over time (where available). The full summary table, designated Table 1, is provided here as a pdf. [update 2013 – this is Version 3]. However, in this format, it still spans two pages, so I composed another table that contains the 2009 status information only (2009 is the most recent available), see Table 2, version 3 below. Viewing the data this way may surprise you.

continue reading

You must be logged in to post a comment.