This a follow-up to my post from last week [“Extirpated polar bears of St. Matthew Island spent five months on land during the summer”]. UPDATED July 24, 2013 [see below]

A new study just published (Robbins et al. 2012, abstract below) suggests that non-pregnant polar bears that lived in Western Hudson Bay during the 1980s and 1990s had enough fat to spend at least 6-8 months on land, making the five months that St. Matthew Island bears spent fasting on shore a less than impressive feat.

Using data on polar bears that fasted around Western Hudson Bay (WHB) in the 1980s and 1990s, Charles Robbins and his colleagues created a model that predicted how long polar bears should be able to fast, given a measured amount of fat.

They concluded from their model results (pg. 1501) that polar bears sampled in Western Hudson Bay in the 80s and 90s had enough fat reserves to survive a fast that varied by sex, as follows:

Pregnant females: 7.7-12.3 months (mean 10.0) [vs. ~8 actual, including den time]

Lactating females with yearling cubs: 2.3-6.1 months (mean 4.2) [vs. ~4 actual]

Males: 5.4-10.6 months (mean 8.0) [vs. ~4 actual]

Note that a pregnant female could not really spend 12 months on shore fasting because she wouldn’t have any time to put on fat for the next year. The point is, however, that an eight month fast was leaving most pregnant WHB females with a good amount of fat left – they weren’t using up all they had (see photo in Featured Quote #7 here).

Lactating females had the lowest reserves of all but many had enough fat reserves to have lasted them through a 5-6 month fast (as the bears on St. Matthew were doing – females with yearling cubs as well as males were present).

This brings to mind one of the stories from my previous post on William Barents’ crew on Novaya Zemyla – that on Feb. 12, 1597, they killed a bear that gave them “at least one hundred pounds of fat.” That’s a lot of fat left on a bear that couldn’t have been eating very much over the previous 3-4 months (the depth of winter at that latitude).

In other words, both this study and the experience of Barents’ men more than 400 years ago suggests that most polar bears have an incredible ability to store fat and that this allows them to fast far longer than is usually assumed possible. Most is not all, however, and of course it is those individuals whose fat storage ability falls short that we hear about.

The authors of this new study, predictably (see abstract below), emphasized that some pregnant and lactating females were at the lower limit of survival (i.e. in the ranges given above, those pregnant females with only enough fat to endure a 7.7 month fast or a lactating female with the reserves to last only 2.3 months, when currently they would routinely spend 8 months and 4 months fasting, respectively, see previous post here).

However, this is hardly surprising. It is to be expected that some females, in any year and in any population, will be less-than-the-best hunters or turn out to have a fat-storage physiology that is not quite adequate. This is called individual variation – an entirely natural feature of any species. And the fact that some animals die because they do not have quite what it takes to survive natural fluctuations in habitat conditions (see previous posts here and here is why population fluctuations in wild animals are quite natural.

For polar bears, longer-than-average summer/fall fasts during longer-than-average ice-free periods mean that individual bears who are less-than-the-best hunters or who don’t have adequate fat storage physiology will die, fail to get pregnant or fail to raise their cubs. The animals that do survive and reproduce successfully, however, will be able to handle subsequent longer-than-average-summers with relative ease.

Longer-than-average ice-free periods also mean that for a short time, the population size will decline. But within a few years or so, the surviving animals – those who can reproduce as successfully as ever – will build the population numbers back up. Just as the bears of Western Hudson Bay appear to have done (see previous post here and Featured Quote #27 here).

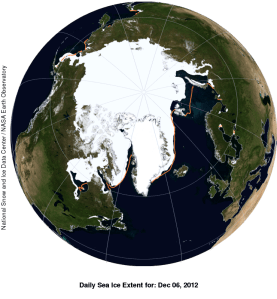

This new study by Robbins and colleagues suggests that if the model results have real-world validity, most of the polar bears in Western Hudson Bay (including pregnant and lactating females) could survive an ice-free season that is 6 months long and that they could handle a 5 month fast with relative ease. However, a 5 month ice-free period is something we haven’t seen yet in Western Hudson Bay, despite the hue-and-cry we hear from some biologists (see previous posts here and here).

UPDATE July 24, 2013

I’ve added this because it seems to me that a few people may not have fully understood the above summary, so I’ve added a bit more detail from the study and my interpretation of it.

In this study (based on models, remember), the mean predicted survival time for all bears was 4.2 months.

As a result, the model results generated by these authors suggested that many (but not all) bears had enough fat reserves to last them through the current 4 month fast but some had enough to endure a 5-6 month fast.

For males in particular, their model results suggested that all males not only had enough fat reserves to survive a 4 month fast (as they currently do) but could have survived a fast of more than 5 months.

While the emphasis on this paper is the ‘catastrophe’ that not all bears would survive a 6 month fast, I should point out that this is their “worst case” scenario – an event that has not even come close to being realized.

While it is true that a few times over the last 40 years, Western Hudson Bay bears have had to endure a fast of 4 months plus three weeks, this length of fasting period has never occurred for more than one year at a time (Stirling et al. 2004; Cherry et al. 2013, see post here. In other words, polar bears have not even begun to approach a sustained 5 month long fasting period.

The authors of this study emphasize only that some pregnant and lactating females would not survive if the length of time onshore during the ice-free period in summer extended to 5 months (from the usual 4 months) and, should that time extend to 6 months, some males would not survive. They stated:

“…some pregnant or lactating females with lower levels of body fat content were already approaching or beyond the constraint of being able to produce cubs and survive the required 8 months of fasting if producing new offspring or 4 months if accompanied by older offspring”

…

“…we estimate that as many as 16% of the adult males would die if fasting lasted for 5.4 months”. [my bold]

They suggest this is in general agreement with a prediction by Molnar et al. (2010) that 28% of adult male bears would die if global warming leads to a 6-month fast.

All of this fails to acknowledge that their results actually predict that most animals (72% of males) would survive the worst conditions they imagined (a 6 month fast), while if a 5-month-plus-2-week fast came to pass, most males (84%) would likely have enough fat reserves to survive. They imply this would be a catastrophe – I call it remarkable survivability.

They do not provide similar quantification for their prediction of mortality among pregnant or lactating females (only adult male numbers were given). They nevertheless say that “pregnant or lactating females and particularly their dependent offspring have the most tenuous future as global warming occurs.”

What they mean is, some percentage (more or less than 84%) of pregnant or lactating females and their dependent young might not survive a 5 month fast and some percentage (more or less than 72%) might not survive a 6 month fast. Again, I wouldn’t call this a catastrophe – I say this is an example of remarkable resilience.

References

Cherry, S.G., Derocher, A.E., Thiemann, G.W., Lunn, N.J. 2013. Migration phenology and seasonal fidelity of an Arctic marine predator in relation to sea ice dynamics. Journal of Animal Ecology 82:912-921. [added July 24 2013]

Robbins, C.T., Lopez-Alfaro, C., Rode, K.D., Tøien, Ø., and Nelson, O.L. 2012. Hibernation and seasonal fasting in bears: the energetic costs and consequences for polar bears. Journal of Mammalogy 93(6):1493-1503. http://www.asmjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1644/11-MAMM-A-406.1

Stirling, I., Lunn, N.J., Iacozza, J., Elliott, C., and Obbard, M. 2004. Polar bear distribution and abundance on the southwestern Hudson Bay coast during open water season, in relation to population trends and annual ice patterns. Arctic 57:15-26. http://arctic.synergiesprairies.ca/arctic/index.php/arctic/article/view/479/509 . [added July 24 2013]

Abstract

Global warming has the potential to reduce arctic sea ice and thereby increase the length of summer–fall fasting when polar bears (Ursus maritimus) lose access to most marine mammals. To evaluate the consequences of such changes, we compared the cost of fasting by polar bears with hibernation by brown bears (U. arctos), American black bears (U. americanus), and polar bears and made projections about tissue reserves polar bears will need to survive and reproduce as fasts become longer. Hibernating polar bears expend energy at the same rate per unit mass as do brown bears and black bears. However, daily mass losses, energy expenditures, and the losses of lean mass are much higher in fasting, active polar bears than in hibernating bears. The average pregnant polar bear living around Hudson Bay during the 1980s and 1990s could fast for 10.0 ± 2.3 months (X̄ ± SD), and the average lactating female with cubs born during the preceding winter could fast for 4.2 ± 1.9 months. Thus, some pregnant or lactating females with lower levels of body fat content were already approaching or beyond the constraint of being able to produce cubs and survive the required 8 months of fasting if producing new offspring or 4 months if accompanied by older offspring. Pregnant or lactating females and their dependent offspring have the most tenuous future as global warming occurs. Thus, we predict a significant reduction in productivity with even modest increases in global warming for polar bears living in the very southern part of their range and are concerned about more northern populations depending on their ability to accumulate increasing amounts of fat.

![A lone polar bear walking on ice [Kathy Crane (NOAA) photo]. We'll call this a metaphor for the expulsion of Mitch Taylor from the PBSG after the Group switched from emphasizing unregulated over-hunting as the primary threat to polar bear conservation to global warming.](https://polarbearscience.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/bear-walking-kathy-crane-noaa.jpg?w=500&h=375)

You must be logged in to post a comment.