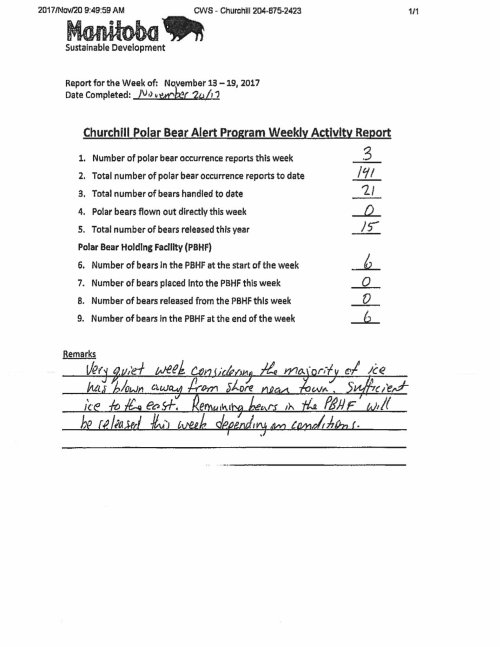

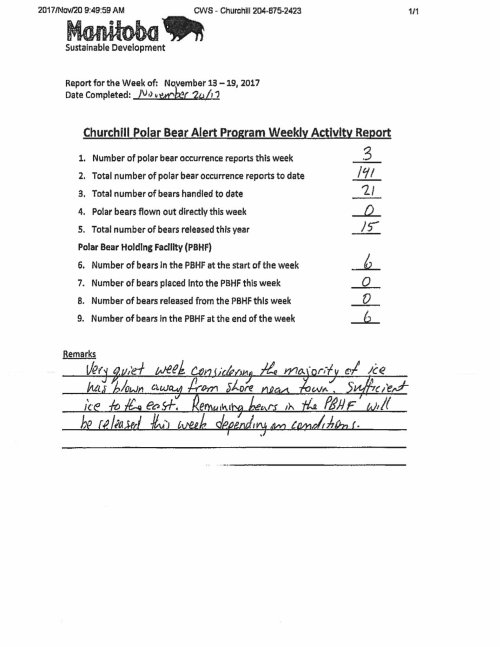

This year, due to an early freeze-up of the sea ice, many polar bears left the Western Hudson Bay area (including Churchill) the week of November 6-12. However, the folks who produce Churchill’s problem polar bear statistics did not generate a report for that week, so we are left with assessing the final freeze-up situation based on the previous report (see it here) and the one they have just released for the week of 13-19 November (below), the 18th week of the season (which began July 10):

The “quiet” week was almost certainly due to the fact that very few bears were still around, having left the previous week.

While it is apparently true that a south wind briefly blew ice away from the area around the town of Churchill, most bears had left by that point and there was plenty of ice to the north and southeast for bears that had congregated outside the town to wait for the ice to form.

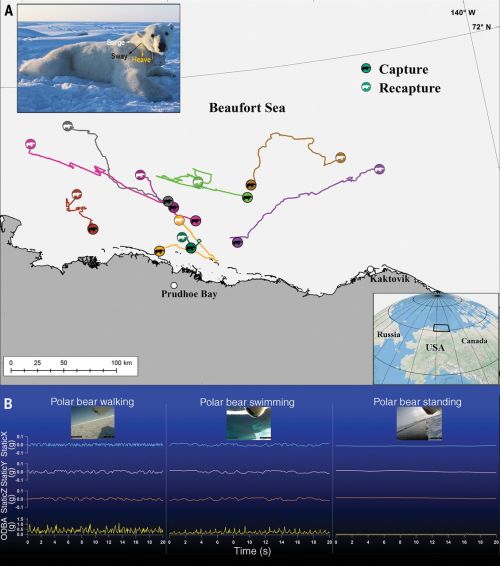

Churchill sits on a point of land (see map below) that makes new ice vulnerable to winds from the south but this year impact was small: the north winds returned within a few days and so did the ice.

By this week there were still a few stragglers that hadn’t left shore but most of these were mothers with cubs, as well as young bears living on their own, who often hold back to avoid dangerous encounters with adult males at the ice edge.

A few adult males that were still in excellent condition after 4 months ashore without food seemed in no particular hurry to resume hunting. In part, this may have been due to the rather foul weather prevalent since the first week of November (with howling winds, low temperatures and blowing snow much of the time).

You can see in the chart below just how much more ice there was for the week of 20 November compared to average — all those dark and light blue areas along the west coast of Hudson Bay (and east of Baffin Bay) indicate more ice than usual. Even Southern Hudson Bay has enough shore ice for bears to resume hunting. Foxe Basin (to the north of Hudson Bay) has less ice than usual (red and pink) but there is still enough ice for polar bears there to begin their fall hunting, as the chart above makes very clear.

Freeze-up and bear movement offshore were about three weeks earlier this year in Western Hudson Bay compared to 2016, which made a huge difference to the number of problem bears in Churchill, see below.

UPDATE 23 November 2017: CIS ice chart for today showing the ice forming in the northwest sector of Hudson Bay

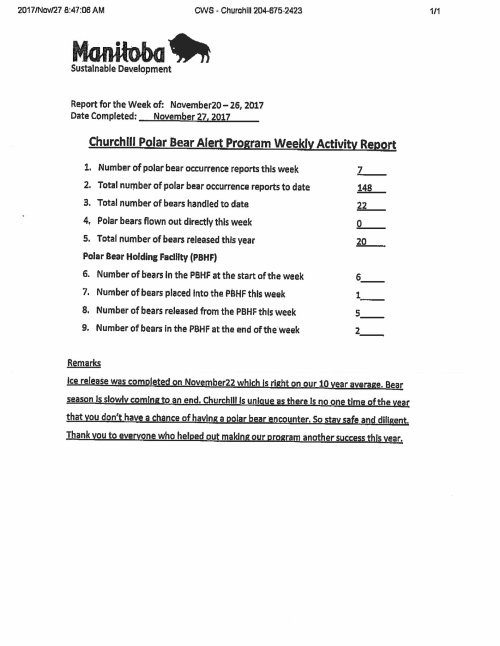

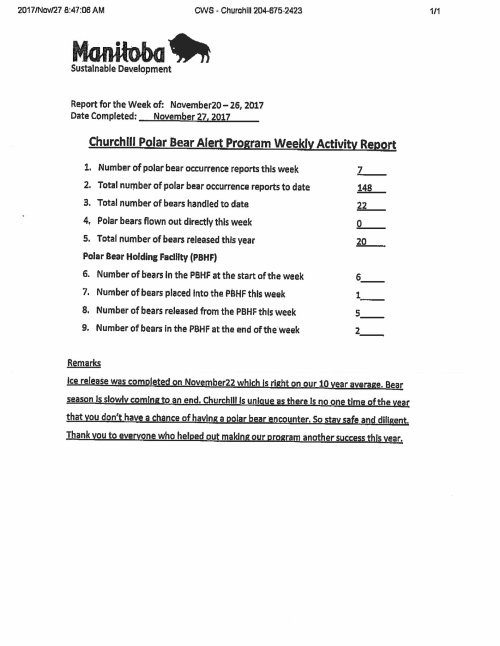

UPDATE 27 November 2017: Final problem polar bear report copied below, issued by the town of Churchill. As noted above, the fact that some bears remained onshore into last week was a very local anomaly not experienced over the rest of the region.

Continue reading

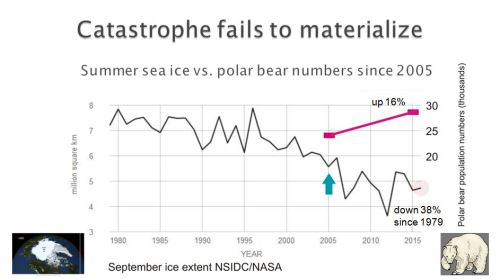

It’s time to abandon the focus on prophesies of impending loss and accept that recovery of polar bears from the over-hunting of last century has continued despite a decade of low summer sea ice (Aars et al. 2017; Crockford 2017; Dyck et al. 2017; SWG 2016; York et al. 2016). Why not focus on the numerous images of

It’s time to abandon the focus on prophesies of impending loss and accept that recovery of polar bears from the over-hunting of last century has continued despite a decade of low summer sea ice (Aars et al. 2017; Crockford 2017; Dyck et al. 2017; SWG 2016; York et al. 2016). Why not focus on the numerous images of

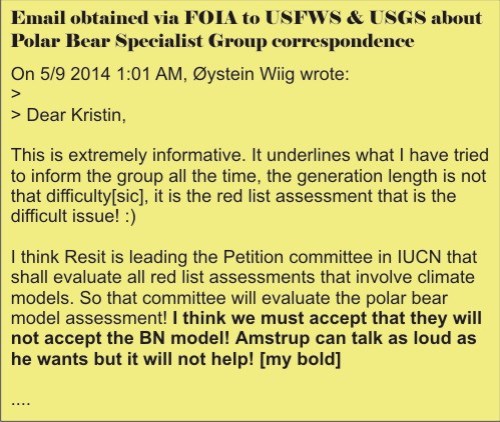

This increase might not be statistically significant but it is most assuredly not the decrease in abundance that was predicted by ‘experts’ such as Steve Amstrup and colleagues (Amstrup et al. 2007), making it hard to take subsequent predictions of impending catastrophe seriously (e.g. Atwood et al. 2016; Regehr et al. 2016; Wiig et al. 2015).

This increase might not be statistically significant but it is most assuredly not the decrease in abundance that was predicted by ‘experts’ such as Steve Amstrup and colleagues (Amstrup et al. 2007), making it hard to take subsequent predictions of impending catastrophe seriously (e.g. Atwood et al. 2016; Regehr et al. 2016; Wiig et al. 2015).

You must be logged in to post a comment.