Winds blew a huge mass of new shorefast sea ice way out into Western Hudson Bay a few days ago (13 November) and very likely took some polar bears with it. This offshore wind phenomenon is common at this time of year – it happened in 2017 – and is often part of the yearly ‘freeze-up’ process for sea ice. But the extent of ice and the distance blown offshore in Hudson Bay this year is impressive.

In previous years, this has happened very early in the freeze-up sequence, well before the ice was thick enough to support polar bears. This year is different: freeze-up was early (starting in late October) and the ice was thick enough off Western Hudson Bay to support bears hunting successfully for seals by the last day of October. By 7 November, most bears had left for the ice, with only a few stragglers left behind – since they were all in good condition due to a late breakup of the ice this summer, there were remarkably few problem with bears in Churchill and some seemed in no hurry to leave once the shorefast ice started to form.

It’s doubtful that any bears out on that wind-blown ice are in any kind of peril. As long as the ice is thick enough to support their weight, they should be fine – and keeping themselves busy catching seals.

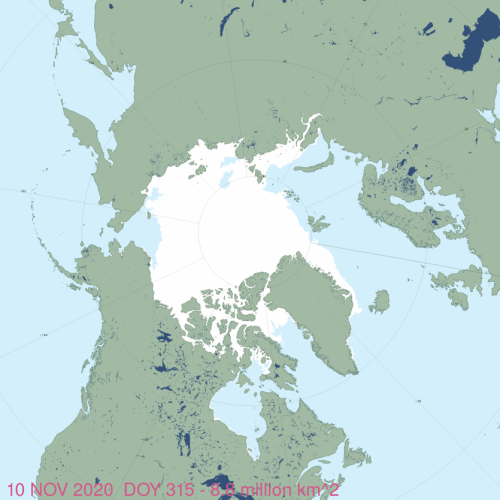

The chart above is from NSIDC Masie for 15 November 2020 (Day 320) – it showed the same large offshore patch of ice the day before. However, only today did the Canadian Ice Service (CIS) chart show even part of the offshore patch (below):

In this case, I’m trusting the Masie chart because it seems the CIS sensors aren’t yet set to pick up ice that’s far offshore, as the detailed stage of development chart for 16 November (below) shows (grey-white ice is 15-30 cm thick, grey ice is 10-15 cm, but see discussion below):

However, after I’d almost given up that we’d hear from Andrew Derocher about his polar bears with still-functioning collars, he posted a tracking map late today (below). Even his chart shows that big patch of offshore ice but he didn’t comment on it at all. It appears that of the 9 collars he deployed on females last year only one is on the ice, well offshore (north of Churchill).

Derocher is still claiming that this is not an early freeze-up year even though it’s clear many bears have already left for the ice and only a few stragglers remain, including most of his collared bears. However, some of his bears are probably pregnant (especially the two furthest inland) and won’t be going anywhere this fall. And we already know that many of Derocher’s collared bears were very late to come onshore in August and having only spent 3 months onshore rather than 4 or 5 months they are used to, may now be in no hurry to leave – especially since they know that seals are to be had out on that ‘very thin’ ice just offshore.

Unfortunately, the Polar Bear Alert Program in Churchill decided not to issue a report for the first week in November (2-8 Nov), so there is no information on the progress of freeze-up and polar bear movements from that authority. There might be one issued tomorrow for the second week (9-15 Nov), if so I’ll post it here.

It’s important to know that even big male bears only need ice that’s about 30 cm thick to hold their weight. And while the newly formed grey ice is technically only 10-15 cm (see the stage of development chart above), the ice offshore this year is very compressed and buckled (see below from 7 November), making it thicker than it might appear on the official ice charts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.