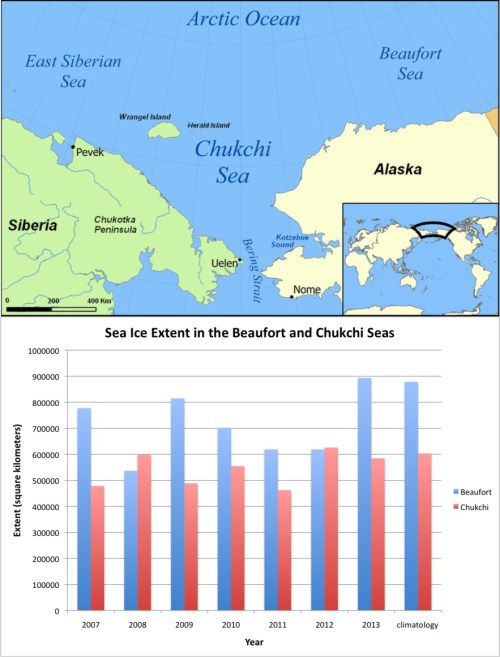

Tracking Beaufort Sea polar bears over the summer — what can it tell us about how important the position of summer sea ice relative to the shoreline in this region is to these bears? Do Beaufort Sea bears get stranded on shore like the polar bears in Davis Strait and Hudson Bay?

Tracking Beaufort Sea polar bears over the summer — what can it tell us about how important the position of summer sea ice relative to the shoreline in this region is to these bears? Do Beaufort Sea bears get stranded on shore like the polar bears in Davis Strait and Hudson Bay?

Polar bear biologist Eric Regehr (with the US Fish & Wildlife Service, or FWS) has a team working with US Geological Survey researchers (USGS) in the southern Beaufort tracking where adult female polar bears go throughout the year. This is part of on-going research in the Beaufort and Chukchi Sea (see previous post here; see also Fish & Wildlife 2009; Polar Bear News 2010 and 2013; Rode and Regehr 2010, pdfs below; and just out, the “accepted” version of the Rode et al. paper discussed here, and announced in my last post here).

The researchers have been posting a summary map at the end of each month on the USGS website showing the tracks of the females they fitted with radio collars the previous spring — for 2013, and back to 2010. They can’t put collars on male bears because their necks are larger around than their heads, so a collar would just slip off.

I’ve posted the July 2013 track map below, which shows all ten bears out on the ice, and the previous month (June 2013) to compare it to (the August map should be out shortly). I’ve included a few maps from 2012 to allow you to compare this year’s results to the situation last summer.

The August tracks should be available after the Labour Day weekend – check back next week to see where the bears have been this month. I’ll post the map here or you can go to the USGS website directly. [UPDATE Sept 4, 2013: The August map is up, posted here.]

You must be logged in to post a comment.