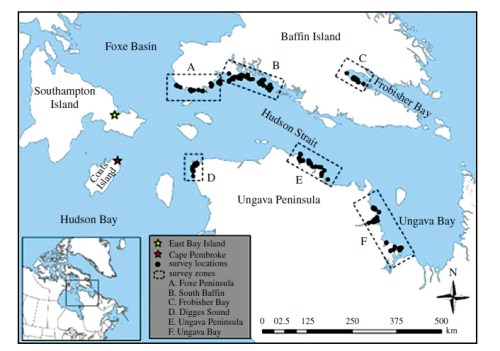

As I outlined earlier this week, Canadian Inuit objected so strenuously to routine mark-recapture methods used by polar bear biologists during the early days of a Foxe Basin population study in 2008 that the work was abandoned and an aerial survey done instead.

In this post, I’ll examine how the polar bear biologists involved reacted to that crisis, which they called a “control of research” issue.

In a published version of a conference paper, co-authored by two of the original investigators of the Foxe Basin mark-recapture study, Lily Peacock and Andrew Derocher (Peacock et al. 2011:374), had this to say:

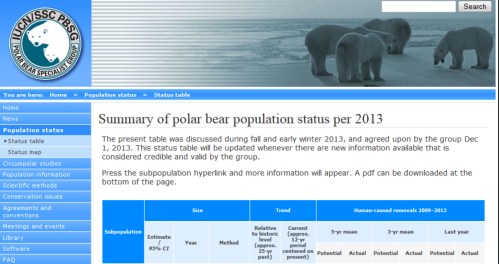

“Control of research is a developing source of conflict. In recent years, some permits for management-oriented research on polar bears were denied by the Government of Nunavut, local hunting and trapping organizations in the Northwest Territories, and by Makivik Corporation in Quebec. Furthermore, in a 2009 resolution, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami opposed the capture of polar bears throughout Canada (available by request from http://www.itk.ca), even though the application of physical marks is one of the most effective methods of population estimation. Co-management is particularly difficult in Nunavut because of the large number of subpopulations (12), which makes it difficult to fund and conduct research.” [my bold]

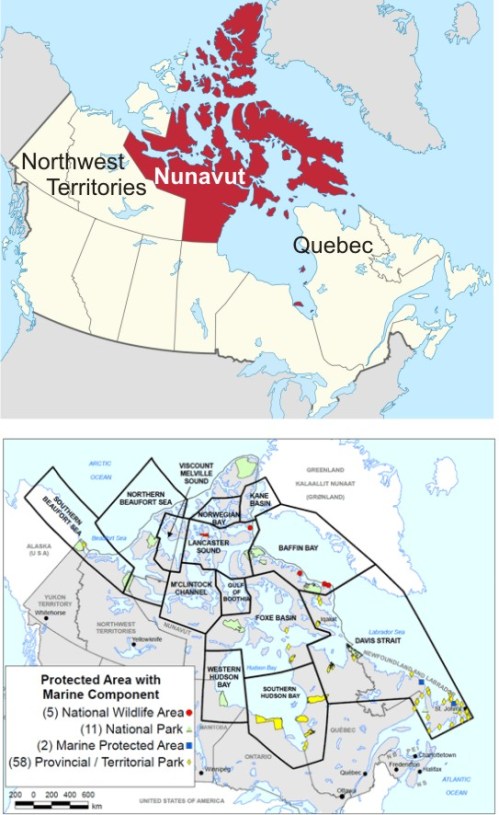

They raised an interesting point – since the Government of Nunavut has the power to insist biologists do more than reiterate that their way of counting bears is the only acceptable way, and because the government can deny permits to projects that don’t measure up, it can lock out traditional polar bear research for virtually all of Canada (the vast majority of Canada’s 13 subpopulations are in Nunavut, see Fig. 1), especially since aboriginal organizations in the Northwest Territories and Quebec have followed Nunavut’s lead.

Figure 1. Territory covered by the Government of Nunavut (top, Wikipedia) and the 13 polar bear subpopulations in Canada (bottom, Environment Canada).

That means if polar bear researchers can’t find a way to make their research mesh with Inuit concerns, they’ll be out of work in Canada. Let’s take a look at their approach and see how well it worked for them — explaining in part the new prominence of aerial surveys for population assessments. Continue reading

You must be logged in to post a comment.