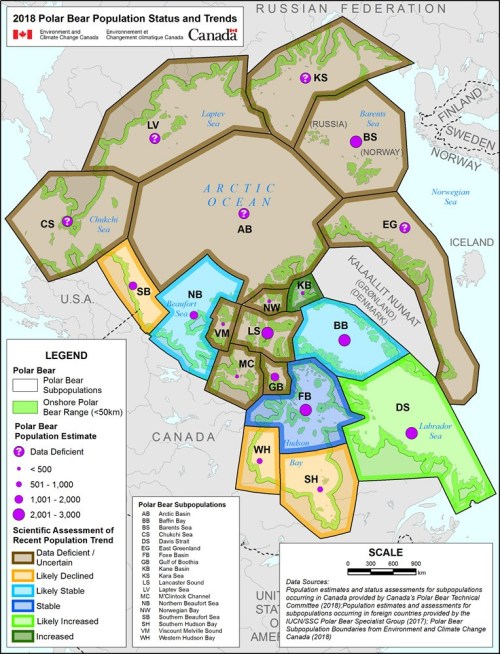

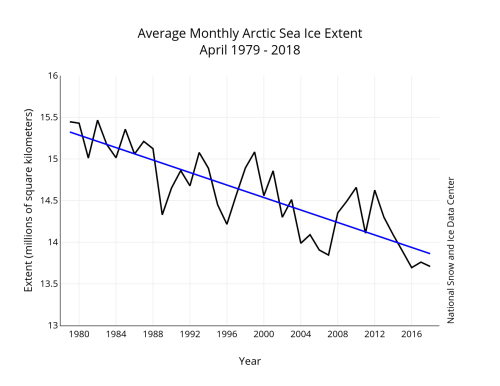

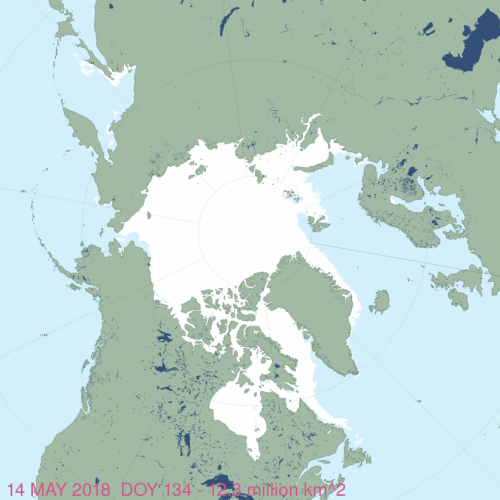

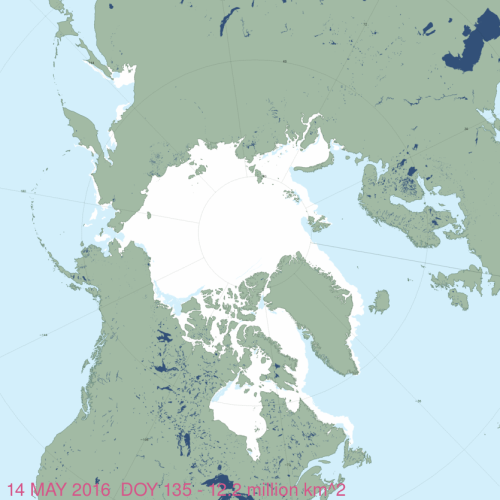

Last week, the Norwegian Polar Institute updated their online data collected for the Svalbard area to include 2017 and 2018 — fall sea ice data and spring polar bear data. Older data for comparison go back to 1993 for polar bears and 1979 for sea ice, showing little to no impact of the reduced ice present since 2016 in late spring through fall.

Here’s what the introduction says, in part [my bold]:

“…The polar bear habitat is changing rapidly, and the Polar Basin could be ice-free in summer within a few years. Gaining access to preferred denning areas and their favourite prey, ringed seals, depends on good sea ice conditions at the right time and place. The population probably increased considerably during the years after hunting was banned in 1973, and new knowledge indicates that the population hasn’t been reduced the last 10-15 years, in spite of a large reduction in available sea ice in the same period.”

See Aars et al. 2017 for details on the 2015 Svalbard polar bear population count, keeping in mind that the subpopulation region is called “Barents Sea” for a reason: only a few hundred individuals currently stick close to Svalbard year round while most Barents Sea bears inhabit the pack ice around Franz Josef Land to the east (Aars et al. 2009; Crockford 2017, 2018).

Continue reading

You must be logged in to post a comment.