The issue of polar bear population density (# of bears per 1000 km2) came up a few posts ago, during my discussion of the new Davis Strait population study by Lily Peacock and colleagues (here). Since the various polar bear subpopulations across the Arctic are so different in size, calculating the density of bears in the various regions generates an interesting metric of how well the regional populations are doing relative to each other.

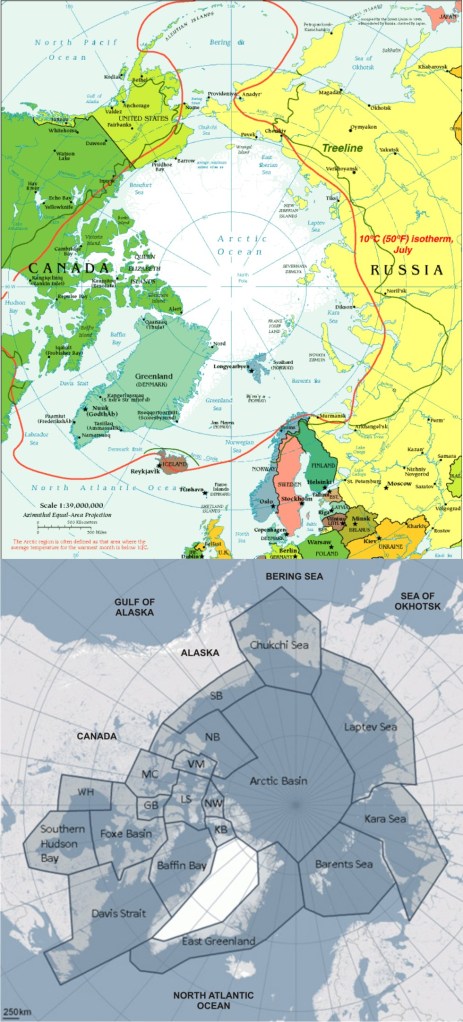

Almost 20 years ago, Taylor and Lee (1995) did just that: they determined the density of polar bears in the various Canadian subpopulations, as of the 1990s. Surprisingly, the ‘leader’ among those, by a wide margin, was one of the smallest in geographic area: the Gulf of Boothia. Located in the central Canadian Arctic (see Figs. 1 and 2 below), in the 1990s, tiny Gulf of Boothia supported a density of 10.4 polar bears per 1000 km2, the highest density of all regions examined.

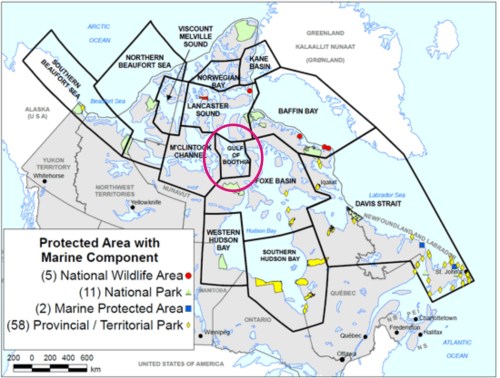

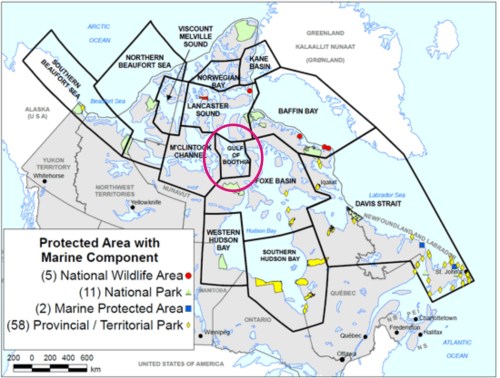

Figure 1. The Gulf of Boothia (circled) is right in the middle of the Canadian Arctic. In terms of geographic area, it is one of the smallest of all 19 subpopulations worldwide: at only 170,000 km2, only the Norwegian Bay and Kane Basin subpopulation regions, also in Canada (just to the north of Gulf of Boothia), are smaller at 150,000 and 155,000 km2 respectively (Vongraven and Peacock 2011). The Gulf of Boothia supports the highest density of polar bears known. Modified from the map of polar bear protected areas provided by Environment Canada.

But this density value for Gulf of Boothia was based on the 1986 population estimate of 900 bears – what is the most current figure?

For that, we need an updated population assessment. That was done in 2000 and it generated an estimate of 1,592 ± 361 bears (Taylor et al. 2009).

Taylor et al. (2009:791) said this about their assessment:

“Our results suggest population size had increased steadily under a harvest regimen of approximately 40 bears/yr” and added, “Barber and Iacozza (2004) found no trends in Gulf of Boothia sea ice conditions or ringed seal habitat suitability indices in the interval 1980-2000.”

In other words, despite there being no trend in either sea ice conditions or habitat for seals – and a yearly harvest of 40 bears – polar bear numbers in the Gulf of Boothia increased significantly (by almost 700 bears) during the twenty years between 1980 and 2000. Even if the 1986 estimate of approximately 900 bears was somewhat less accurate than the more recent one, the fact that tiny Gulf of Boothia can support 1,592 bears is surely a remarkable feat.

Using this new population estimate and the same area of ‘available habitat’ used by Taylor and Lee in 1995, I calculated the most recent density at a spectacular 18.3 bears per 1000 km2! [note this is exactly what Peacock et al (2013) did to get their density value of 5.1 bears/1000 km2, discussed here.] But I didn’t update just Gulf of Boothia, I did them all.

The updated density values for Gulf of Boothia and several other Canadian subpopulations are listed in Table 1 below. Note that aside from Davis Strait, as far as I know these density figures have not been published elsewhere: you’re seeing them here for the first time.

Continue reading

![A polar bear near Thule, NW Greenland. Note the decidedly chubby back end on this bear, who looks well prepared for winter. Photo by Robin Davies. [details at my Quote Archive, Featured Quote #6]](https://polarbearscience.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/polarbearatthulerobindavies-500x349-sm.jpg?w=500)

You must be logged in to post a comment.