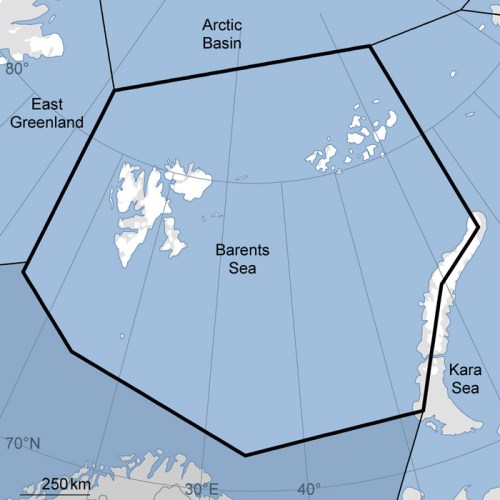

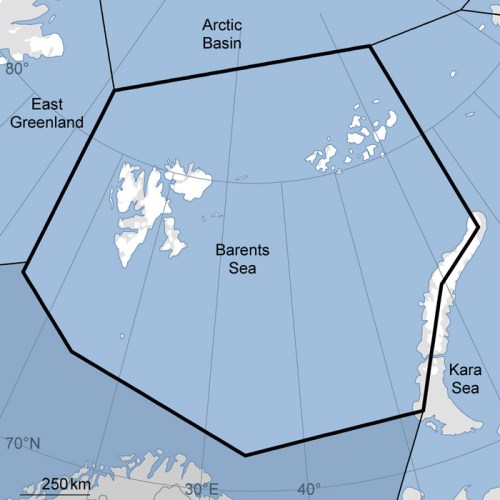

Figure 1. NSIDC sea ice extent at March 8, 2014 (a “MASIE” product), with labels added. Click to enlarge.

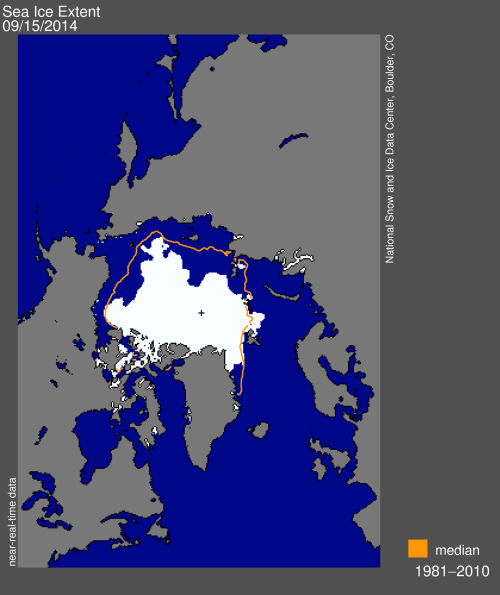

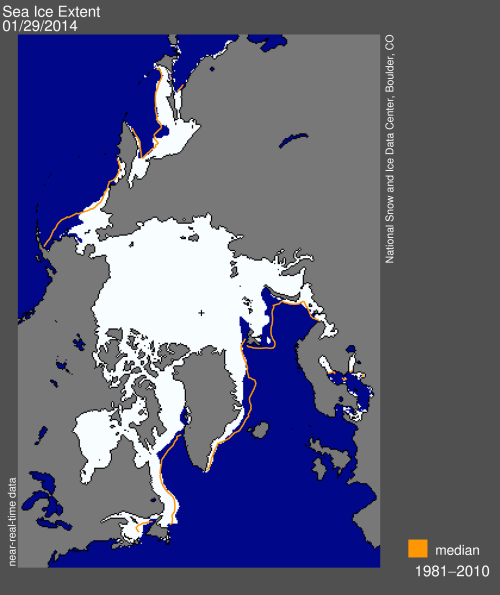

In its end of February report, the US National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) noted that Barents Sea ice was below average for this time of year (see Fig. 1 above, and Fig. 5 below) but suggested this was primarily due to natural variation driven by the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO):

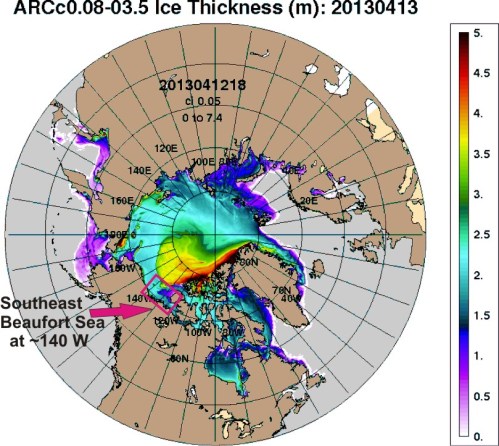

“The Barents Sea has experienced consistently low extents, particularly in winter, and this year has been no different. While the Barents and Kara seas normally have close to 2 million square kilometers (772,000 square miles) of ice in February, recent years have seen 500,000 square kilometers (193,000 square miles) of ice extent or lower. This year, the Kara Sea is near average, but the Barents Sea remains low (Figure 4a). Unlike other regions in the Arctic, longer records of Barents Sea ice extent exist from records of fishing, whaling, and other activities. A recent paper (Miles et al., 2013 [2014, now in print]) examined these records, along with paleoproxy data, to examine extent over the past four hundred years. They found a 60- to 90-year cycle in Barents and Greenland seas ice extent related to the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO); the AMO is a basin-wide cycle of sea surface temperature variability similar to the El Niño and La Niña cycles in the Pacific, but varying over much longer periods. This research shows that in addition to the warming trend in the Arctic, some sea ice regions are likely also responding to natural climate variability.” [my bold]

The paper they cite (Miles et al. 2014, discussed elsewhere in December 2013 here) described the AMO this way:

“The AMO is a coherent pattern of basin-wide sea surface temperature (SST) variations with a period of roughly 60–90 years. ..Paleoenvironmental studies suggest that the AMO has persisted through previous centuries [Gray et al., 2004] and even millennia [Knudsen et al., 2011].”

Note that Miles and colleagues were looking at ice records on or around the sea ice maximum in winter/spring.

The Polar Bear Twist: Norwegian biologists Jon Aars and Magnus Andersen, who I’ve discussed before, have pointed out that the condition of polar bear males and females around Svalbard (Fig. 2) they examined over the last 20 years varied with the AMO and sea ice levels in spring and early summer. [research results posted at the website for Environmental Monitoring of Svalbard and Jan Mayen (MOSJ), Norwegian Polar Institute].

Figure 2. The Barents Sea polar bear subpopulation boundaries, courtesy the IUCN Polar Bear Specialist Group. Svalbard is the largest archipelago, closest to the East Greenland Sea.

That makes a lot of sense to me, given that spring/early summer is the most critical feeding season for polar bears because it’s when fat young seals are most easily available.

It also makes sense to me that you may need a record hundreds of years long to understand the natural variability of Arctic Sea ice in its various regions. Recall that natural variation, not global warming, is now being used to explain the large variation in annual sea ice cover in the Bering Sea (home to Chukchi Sea polar bears). Continue reading

You must be logged in to post a comment.