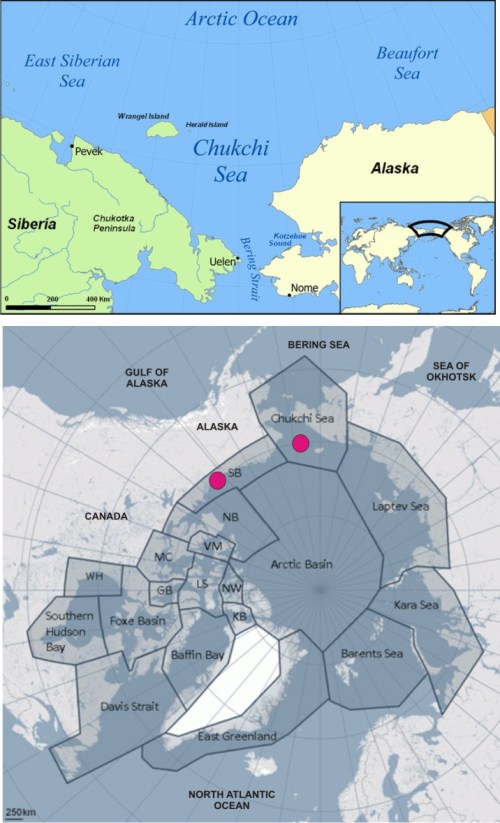

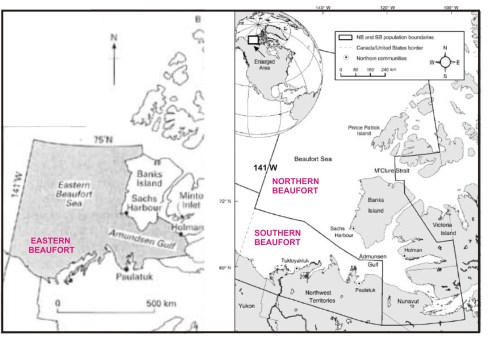

A bit more good news about polar bear populations, this time from an abundance study in the Southern Beaufort Sea. A paper released yesterday showed a 25-50% decline in population size took place between 2004 and 2006 (larger than previously calculated). However, by 2010 the population had rebounded substantially (although not to previous levels).

All the media headlines (e.g. The Guardian) have followed the press release lead and focused on the extent of the decline. However, it’s the recovery portion of the study that’s the real news, as it’s based on new data. Such a recovery is similar to one documented in the late 1970s after a significant decline occurred in 1974-1976 that was caused by thick spring ice conditions.

The title of the new paper by Jeffery Bromaghin and a string of polar bear biologists and modeling specialists (including all the big guns: Stirling, Derocher, Regehr, and Amstrup) is “Polar bear population dynamics in the southern Beaufort Sea during a period of sea ice decline.” However, the study did not find any correlation of population decline with ice conditions. They did not find any correlation with ice conditions because they did not include spring ice thickness in their models – they only considered summer ice conditions.

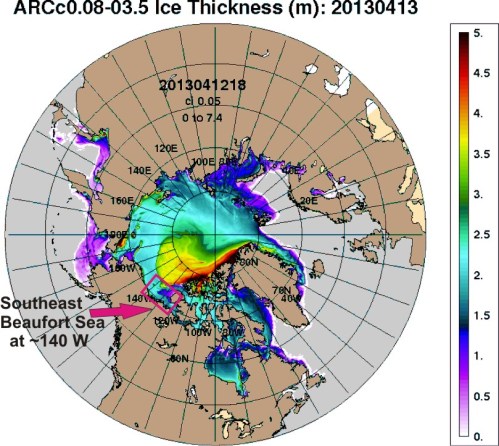

I find this very odd, since previous instances of this phenomenon, which have occurred every 10 years or so since the 1960s, have all been associated with thick spring ice conditions (the 1974-76 and 2004-2006 events were the worst). [Another incident may have occurred this spring (April 2014) but has not been confirmed].

Whoever wrote the press release for this paper tried hard to suggest the cause of the 2004-2006 event might have been “thin” winter ice caused by global warming that was later deformed into thick spring ice, an absurd excuse that has been tried before (discussed here). If so, what caused the 1974-1976 event?

It seems rather unscientific as well as implausible to even try to blame this recent phenomenon on global warming. However, neither the authors of the paper or the press release writers seemed to want to admit that 2-3 years of thick ice development in the Southern Beaufort could have been the cause of the population decline in 2004 (as for all of the previous events). No, that wouldn’t do, not in the age of global warming.

So, we are left with this equally absurd conclusion from the author:

“The low survival may have been caused by a combination of factors that could be difficult to unravel,” said Bromaghin, “and why survival improved at the end of the study is unknown.”

I’ve summarized the paper to the best of my understanding (there was a lot of model-speak to wade through), leaving out the prophesies of extinction, which in my opinion don’t add anything.

UPDATE November 19, 2014: Don’t miss my follow-up post, with some startling new information, “Polar bear researchers knew S. Beaufort population continued to increase up to 2012“

Continue reading

You must be logged in to post a comment.